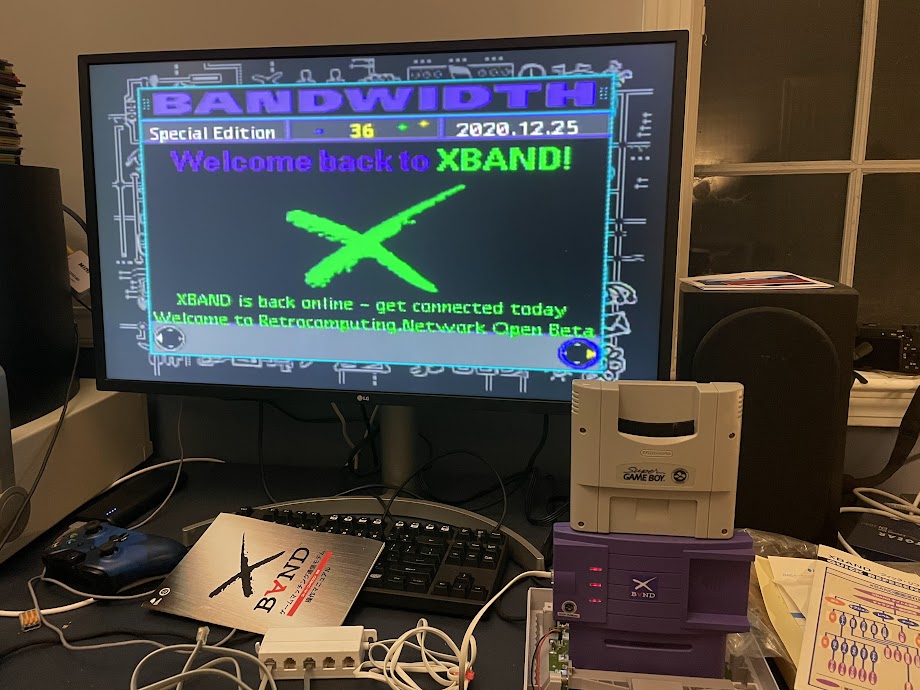

XBAND Trials

The XBAND was a third-party modem produced by Catapult Entertainment for the Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis in the mid-90s. It enabled multi-player support over phone lines by being placed in between the game cartridge and console. The service has been shut down for many years, but has recently been revived by hobbyists. I worked with a group trying to improve service quality. To understand what we did, you need to know a bit about how the service worked. Alice tells her XBAND that she wants to play online. The modem dials Catapult’s phone number, and establishes a brief modem connection, where news and mail is exchanged, and Alice’s phone number is registered as looking for a game. Her cartridge then ends the connection and hangs up. Bob selects he wants to play online. His cartridge performs a similar connection procedure to Alice, but since Alice is currently waiting for a game, the central server gives his cartridge Alice’s phone number and instructs it to dial out. His cartridge then hangs up the connection, and calls Alice’s phone number. Alice’s modem answers the call, and the two modems establish a connection. This peer to peer structure has a few effects.

- Along with the monthly charge of XBAND service, players would have to pay long distance charges to their phone company if they wanted to play outside of their area code.

- Catapult tried to subsidize these calls by having the modem contact a calling card-esq service, however I believe they stopped it since players were intercepting the access PIN dialed by the cart and using it for themselves

- Catapult’s servers only talk to the cartridges briefly, increasing capacity and saving money

- Due to the circuit switched architecture of the 1990s telephone infrastructure, a telephone connection was quite low latency (mostly due to speed of light lag) and extremely low jitter. This is essential to the operation of the XBAND. Since they were modifying game ROMs, there was essentially no “Netcode” as we think about it today, and is more akin to just sending controller inputs to the other console. Sync delays in some games was done by toggling between progressive and interlaced scanning during the VBI I believe. A few years ago, some amazing work was done to create a recreation of the catapult servers to allow XBANDs to connect again. I joined the project after, so I am unsure of the technical details, but it involved PHP and AppleTalk, so strap in. Important to this story, it uses the PBX software Asterisk to interface with telephony in two ways. The most common way is using an ATA, which is a hardware box that has an RJ11 phone jack and an Ethernet connection on it. They are used to connect classic telephones to VOIP networks, and are basically added as lines to the Asterisk server. Both phases of the connection were performed as basically dialing extensions on a PBX, and all tunneled through SIP. The roofgarden servers also have a POTS telephone number through a SIP broker. If both players have landline telephone service, they can also play as someone would in the 90s, just using a different access number. This has a major problem however. SIP connections run over IP, which has significantly more latency and jitter than circuit switching. Even landline connections are almost always packetized at some point in the chain. To fight this, I came up with two plans

- Attempt to replace SIP with an audio protocol that prioritizes low latency

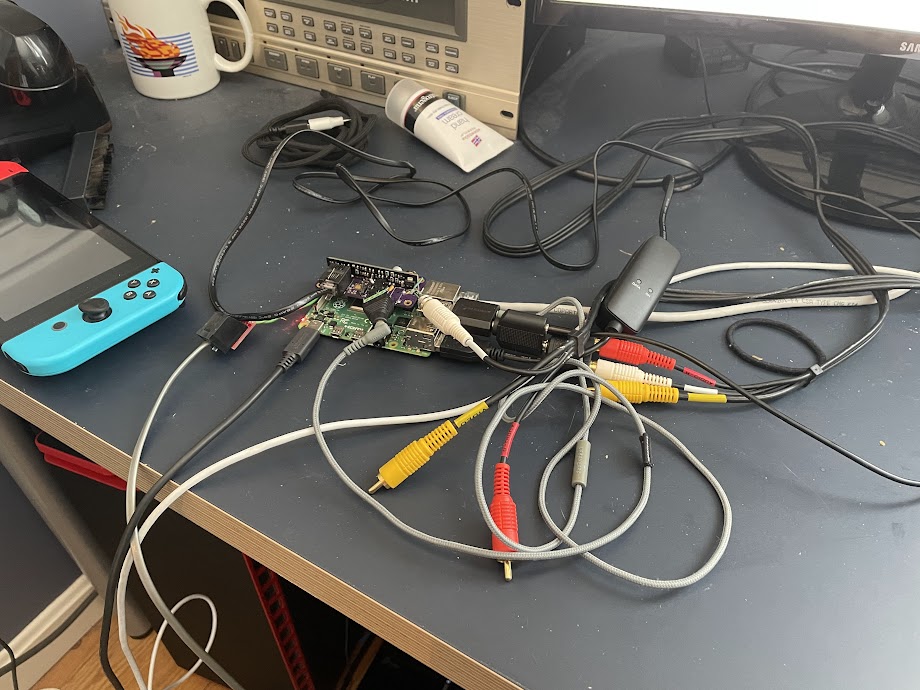

- Convert the modem traffic back to data locally, and tunnel that data across the internet rather than the audio. Attempt one was done with a PCB I designed that converted that converts a telephone line into speaker/line jacks. These were plugged in, along with a USB dialup modem, to a Raspberry Pi. The connection sequence was as follows for the second registered party, which was implemented via Python

- The XBAND modem goes off hook, and dials the old Catapult phone number

- The local dialup modem intercepts this, answers the call, and passes the data to the Roofgarden servers over TCP

- The XBAND, now knowing the opponent details, hangs up the modem call, and dials the opponent’s phone number

- The local pi, knowing this is a game call, starts a Jacktrip instance, and creates an audio bridge over the internet to the opponent. I had a whole scheme of encoding IPv4 addresses in a phone number, but the project never got far enough for that to be relevant Theoretically, this would be the simplicity of a VoIP call, but with lower latency. In practice, this never worked for a few reasons.

Jacktrip bridge testing

- My testing infrastructure wasn’t great, and I was sending untested hardware to untrained (but very helpful people!) for alpha testing. Not a good idea

- I think the inherent lag and jitter of the modern internet just can’t be overcome, as Jacktrip is the best case

The second attempt was similar to the first, but instead of jacktrip tunneling the audio signal of the xband modem, a local modem would demodulate the signal back into a 2400 baud binary signal, which would be passed over the internet. After all, theres no sense in converting the data to audio, and pass it over, if it’s binary data to begin. This also got pretty far in development, a lot of folks in the community have hardware capable of it since there’s a similar scheme for Sega Dreamcast games, so there were a few hours of phone calls trying to get hardware to sync. Only after all of that did I think to do a proof of concept which was to have a modem on my desk call another modem on my desk, send it a piece of information, bounce that packet off a server on the internet, and have it traverse both modems.

Roundtrip Modem Testing The round trip time of this best-case scenario was still worse than the minimum latency requirements, so that part was scrapped too. The XBAND was a completely unique piece of information, and it’s so clear that its creators deeply cared about this product. It’s something that I have become somewhat of an expert on, which makes me feel like I know a secret few others do. I’d still like to connect two xbands together locally to truly recreate the experience, so if anyone out there has a super nintendo and a copy of mario kart in the boston area, hit me up. I also recorded some games played over a landline for posterity, as VHS recordings of XBAND games is what got me interested in the first place. Special thanks to natalie, spinthwomp, CMA, and everyone else who helped with this project.